E-mail: font@focusonnature.com

Phone: Toll-free in USA 1-888-721-3555

or 302/529-1876

Website: www.focusonnature.com

|

PO Box 9021,

Wilmington, DE 19809, USA E-mail: font@focusonnature.com Phone: Toll-free in USA 1-888-721-3555 or 302/529-1876 Website: www.focusonnature.com |

Rare Birds in the

Caribbean

noting those found

during Focus On Nature Tours

Followed by a List of West Indian Birds

that have become Extinct

In the listing that follows, endemics to the

various islands are noted.

Upcoming FONT Birding & Nature Tours in the Caribbean FONT Past Tour Highlights

A Caribbean Bird-List & Photo Gallery, in 2 Parts:

Part 1: Guineafowl to Hummingbirds

Part 2: Trogons to Buntings

Bird-Lists for:

Cayman Islands

Jamaica

Lesser

Antilles Puerto

Rico Dominican Republic

![]()

Islands where birds have been seen during FONT tours are noted in the following list.

SPECIES OF CARIBBEAN BIRDS

Classified as CRITICALLY THREATENED:

Cuban Kite Ridgway's Hawk

Zapata Rail Grenada Dove Puerto Rican

Amazon

Bahama Oriole

Montserrat

Oriole

Classified as ENDANGERED:

Black-capped Petrel

Gundlach's Hawk Blue-headed Quail-Dove Imperial

Amazon

Bay-breasted Cuckoo

Puerto Rican Nightjar Giant

Kingbird Bahama Swallow

Zapata Wren LaSelle Thrush

White-breasted

Thrasher Whistling Warbler

Yellow-shouldered Blackbird Jamaican Blackbird

Cuban (or Zapata) Sparrow

Saint Lucia Black

Finch Hispaniolan Crossbill

Red Siskin Eastern Chat-Tanager

Classified as VULNERABLE:

West

Indian Whistling Duck Ring-tailed Pigeon

White-fronted Quail-Dove Gray-headed Quail-Dove

Hispaniolan

Parakeet Hispaniolan Amazon

Yellow-billed Amazon Black-billed Amazon

Red-necked Amazon Saint Lucia

Amazon Saint Vincent Amazon

Yellow-shouldered Amazon

Fernandina's

Flicker White-necked

Crow Golden Swallow

Forest Thrush

Bicknell's Thrush

Elfin Woods

Warbler Cerulean Warbler Hispaniolan Highland Tanager

Western Chat-Tanager

Classified as NEAR-THREATENED:

Black Rail

Caribbean Coot Piping Plover Buff-breasted

Sandpiper White-crowned

Pigeon

Plain Pigeon Crested Quail-Dove Rose-throated Amazon Least

Poorwill Bee Hummingbird

Hispaniolan

Trogon Guadeloupe

Woodpecker Hispaniolan Palm Crow Blue

Mountain Vireo

Cuban Solitaire Golden-winged Warbler Vitelline

Warbler Barbuda Warbler

Bahama

Warbler

Kirtland's Warbler

Saint Lucia Oriole Gray-crowned Palm Tanager

Species that are either now EXTINCT or assumed to be:

Jamaican Petrel Eskimo Curlew

Cuban, or Hispaniolan Red

Macaw (& other psittacids)

Jamaican Poorwill

Brace's Hummingbird

Cuban Ivory-billed Woodpecker

Grand Cayman Thrush Bachman's Warbler

Semper's Warbler

![]()

Species in the Caribbean classified as CRITICALLY THREATENED:

1 CUBAN KITE ______

(endemic to Cuba)

Chrodrohierax wilsonii

The Cuban Kite, with an isolated and very small population on Cuba, has been

considered a subspecies of the Hook-billed Kite, Chondrohierax

uncinatus.

2 RIDGWAY'S HAWK

______ Dominican

Republic

(endemic)

Buteo ridgwayi

Only on Hispaniola (and now only in the Dominican Republic), the

Ridgway's Hawk is said to

have once been widespread throughout the island. Certainly it was more common

than it is today.

Now, in fact, it is very rare, with a total population estimated as being from

50 to 250 birds.

Most recent records of the Ridgway's Hawk have been in the northeastern Dominican Republic in the

area of the Los Haitises National Park. Surveys in that park in 2002 and 2003,

found up to 37 pairs. Several nests were discovered and monitored.

However, elsewhere in the country very few individuals could be found of this

apparently still-declining raptor.

A few birds have also been recorded,

in recent years, in the southwestern Dominican Republic, in the area of the

Sierra de Baoruco (Baoruco Mountains). A nest was found in that region back in 1997.

3 individual Ridgway's Hawks were seen during the FONT Dominican Republic tour in March 2003,

in the southwestern part of the island. The birds were not far from us, as they were

seen one morning, in rising thermals as they circled low above a valley.

3 ZAPATA RAIL ______ (endemic to Cuba)

Cyanolimnas cerverai

4 GRENADA DOVE ______

Grenada (endemic)

Leptotila wellsi

The Grenada Dove is closely related to the Gray-fronted Dove of Central & South America,

Leptotila rufaxilla. The two have been said by some to be conspecific.

5 PUERTO RICAN AMAZON

(or Puerto Rican Parrot) ______ Puerto Rico

(endemic)

Amazona v. vittata (a second subspecies on Culebra Island,

A. v. gracilipes, is now

extinct)

The Puerto Rican Amazon (or Puerto Rican

Parrot) is now the rarest of the Caribbean island

amazons. The bird has

been critically endangered for years. Formerly occurring in various areas of

Puerto Rico, it has become very localized in a small, hilly area of

northeastern Puerto Rico.

In 1975, there were only 13 Puerto Rican Amazons in the wild. From that unlucky

low, the number about 10 years later was 30. In the late 1990s, the global

population was 44 in the wild and 87 in captivity.

During our March 2004 tour in that part of Puerto Rico, we saw 1 wild Puerto

Rican Amazon. It was in the area of the facility with the birds in the captive

breeding program. The bird apparently was drawn to the noise of the caged birds'

calls in the afternoon. It appeared to be a bird preferring to forfeit its

lonely wildness for companionship in captivity (Parrots are social birds).

The Puerto Rican Amazon has been seen during 11 FONT tours since 1990. The most

seen were 12 individuals in March 1996. Prior to March 2004, our most-recent

sighting was in

March 2000.

The Puerto Rican Amazon has come close to following the fate of the amazon

parrots that once were in Guadeloupe and Martinique, and the macaws that were in

Cuba and elsewhere in the Caribbean - see the listing of "EXTINCT BIRD SPECIES"

before the end of this list.

7 BAHAMA ORIOLE ______ Bahamas (endemic)

Icterus northropi

In 2010, four endemic subspecies of what was the Greater Antillean

Oriole were elevated to being full species:

the Hispaniolan Oriole, Icterus dominicensis

the Puerto Rican Oriole, Icterus portoricensis

the Cuban Oriole, Icterus melanopsis

the Bahama Oriole, Icterus northropi

Shortly thereafter, in 2011, the Bahama Oriole was classified by Birdlife

International as "critically endangered".

Historically, the Bahama Oriole was found on the Bahamian islands of

Abaco and Andros. For unknown reasons, the Abaco population disappeared during

the early 1990s, and there is evidence that the Andros population is in decline.

Recent surveys (in 2010) of the three main islands forming Andros recorded 81

orioles on North Andros, 22 on Mangrove Cay, and 24 on South Andros, making a

total of 121 birds. Based on these figures, the estimated total population is

fewer than 250 individuals.

The survey found that the orioles occur mainly in human-altered habitat, such as

residential and agricultural land, during the breeding season.

However, nearby natural habitat, particularly coppice (dry-broadleaf forest),

appears to be important, year-round, for the survival of the Bahama Oriole.

8 MONTSERRAT ORIOLE ______ Montserrat

(endemic)

Icterus oberi

Species in the

Caribbean classified as ENDANGERED:

9

BLACK-CAPPED PETREL

______ Puerto Rico (during

a FONT pelagic trip)

Pterodroma h. hasitata

The Black-capped Petrel has a very small, fragmented, and declining breeding

range that's only on some Caribbean islands.

It is now known to nest in Haiti and the adjacent Dominican Republic, where

there are an estimated 1,000 breeding pairs, mostly on the Massifs de la Selle

and de la Hotte in southern Haiti.

In the Dominican Republic, where nesting occurs in the Sierra de Baoruco (Baoruco

Mountains), nests are in cliffs only at a high altitude of almost 7,000 feet

above sea level.

In the Lesser Antilles, Black-capped Petrels have recently been

found on Dominica,

and over nearby offshore waters, suggesting that the species may nest on that

island.

968 birds were found there during a survey that began in January 2015, and

hopefully as research continues, it will be found that the species nests high in

the forested mountains of Dominica, where the last confirmed nesting was

in 1862.

The bird is now believed to be extinct on Guadeloupe, where it was common in the

19th Century. It may have bred, in the past, on Martinique.

Even during the breeding season, the Black-capped Petrel is highly pelagic,

occurring at that time as far from Caribbean islands as in the area of the Gulf

Stream off North Carolina, USA.

Birds disperse over the Caribbean Sea and

Atlantic Ocean from that area (off North Carolina) to waters off northeast

Brazil, but the at-sea range is said to have recently

contracted.

As noted, nests are in burrows in cliffs, in montane forest, at about 1,500 to

2,300 meters (4,500 to nearly 7,000 feet) above sea level. Nesting is colonial,

and begins in December.

As also noted, birds often commute long distances between breeding sites in the

mountains and foraging sites at sea. When doing so, the Black-capped Petrel is

primarily nocturnal and crepuscular. It feeds on fish, invertebrate swarms,

fauna associated with Sargassum seaweed, and squid. Birds are attracted to

localized upwellings, where the mixing of oceanic waters produces patches of the

sea that are rich in nutrients.

A single Black-capped Petrel was seen during the first FONT Caribbean pelagic trip, on February 8,

1996, off the west coast of Puerto Rico. The sighting was late in the

day.

A Black-capped Petrel

photographed during a FONT tour

Closely related to the Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata, has been (or

was) the Jamaica Petrel, Pterodroma caribbaea, that has now been presumed, for

years, to be extinct. It was last collected in 1879.

The bird has been said by some to be an all-dark subspecies of the BLACK-CAPPED

PETREL, but it has now been most often been said to be a separate species. (See

notes that follow under "Extinct Bird Species in the West

Indies".)

10 GUNDLACH'S HAWK ______

(endemic to Cuba)

Accipiter gundlachi

11 BLUE-HEADED QUAIL-DOVE ______ (endemic to Cuba)

Starnoenas cyanocephala

12 IMPERIAL AMAZON (or Imperial Parrot)

(the "Sisserou")

Puerto Rican Nightjar

15 GIANT KINGBIRD ______

(endemic to Cuba)

Tyrannus cubensis

16 BAHAMA SWALLOW ______ Bahamas

(endemic)

Tachycineta cyaneoviridis

17 ZAPATA WREN ______ (endemic to Cuba)

Forminia cerverai

18 LA SELLE THRUSH ______ Dominican Republic

(endemic to Hispaniola)

Turdus swalesi

The shy LaSelle Thrush was discovered in mountains in southern Haiti, known as

the Massif de la Selle, in 1927. It was not recorded elsewhere until 1971, when

it was found to be in the Bahoruco Mountains in the southwest Dominican

Republic.

In 1986, it was determined that the LaSelle Thrush population that had just recently been

found in the Central Mountains of the Dominican Republic was a different

subspecies, T. w. dodae.

The LaSelle Thrush occurs above 1300 meters above sea level in dense understory

of moist montane broadleaf forest. It is occasionally in pine forest, but only

where there is a well-grown broadleaf understory (which is rare in the pine

woods habitat of the Dominican Republic).

Even though many of the thrushes in the world in the Turdus genus are obvious,

and easy to see, the LaSelle Thrush, Turdus swalesi, is not. As noted, it is a

shy, very reclusive bird.

The bird mainly forages on the ground for earthworms, insects, and fruit.

In the mountainous Sierra de Baoruco, in the southwestern Dominican Republic,

close to Haiti, the LaSelle Thrush is restricted to isolated patches of its

preferred habitat.

In Haiti, all suitable forest may have disappeared from the species's range, and

thus the bird may be extirpated from that entire country where it was first

discovered less than 100 years ago. The LaSelle Thrush was formerly common at

the La Visite National Park in Haiti, but now its status there is unclear.

The recently-discovered race, T. w. dodae, in the western and central Dominican

Republic, occurs in the Sierra de Neiba and the Cordillera Central.

The LaSelle Thrush has been found during FONT tours in the Sierra de Baoruco

(near Haiti, and unfortunately near an area of increased human disturbance).

But, to date, it has not been found during a FONT tour in the Cordillera

Central.

19 WHITE-BREASTED THRASHER

______ Saint Lucia

Ramphocinclus brachyurus

The White-breasted Thrasher has an extremely small range and population on the

two Lesser Antillean islands of Saint Lucia and Martinique. On each island, there

is a different subspecies.

On Saint Lucia, the race R. b. santaeluciae inhabits low scrubby woodland in

ravine bottoms with dense stands of thin-trunked riparian trees. It forages on

the ground for small invertebrates, and sometimes small frogs and lizards. But

the bird only occurs in Saint Lucia on a small portion of that island (that

itself is not big!). The range on Saint Lucia is on the drier (Atlantic) side of

the island between the Marquis river valley and the Frigate Island Refuge.

In 1992, the population on Saint Lucia was said to be 46 pairs. That indicated

an annual decline of over 4 per cent in the 5 years since 1987. In 1997, the

Saint Lucian population was estimated to be just over a hundred individuals.

During that year, 1997, on Saint Lucia, nesting success was 44 per cent,

suggesting a rather normal level of nest-predation for a tropical

passerine.

However, due to predation of flightless young (on the ground) and habitat loss,

the sad decline of this very rare bird may well be continuing on Saint Lucia and

Martinique.

On Martinique, the population has been about 40 pairs on the Caravelle Peninsula.

The White-breasted Thrasher has been seen during nearly all of the 15 FONT tours

on Saint Lucia.

20 WHISTLING WARBLER

______ Saint Vincent

(endemic)

Catharopeza bishopi

The Whistling Warbler is an attractive little bird that exists only on the one

little island of Saint Vincent. And on that island, it occurs just in three

areas, where the favored habitat of the bird has been declining. The 3 areas are

the Colonaire and the Perserence Valleys, and Richmond Peak.

A total of about 2,000 singing males was estimated in 1986. Regarding the

decline of suitable habitat, just noted, it diminished from 140 square

kilometers in the early 1900's to about 80 square kilometers in 1986.

The habitat favored by the Whistling Warbler is dense undergrowth and

vine-tangles in primary rainforest, and also: palm brake, elfin forest,

secondary growth and borders. But the primary rainforest and palm brake is the

most important, holding 80 per cent of the population.

The bird is found at elevations of 300 to 1,100 meters above sea level, but

mostly below 600 meters.

Eggs are laid between April and July.

A central part of Saint Vincent was designated as a wildlife reserve in 1987,

and this protection of habitat can be a benefit to the Whistling Warbler.

The Whistling Warbler of Saint Vincent

21 YELLOW-SHOULDERED

BLACKBIRD ______ Puerto Rico

(endemic)

Agelaius x. xanthomus

(a second Puerto Rican subspecies is on Mona Island)

The Yellow-shouldered Blackbird was formerly widespread on the island of Puerto

Rico, but now it is restricted to the extreme southwest portion of the

island.

A second subspecies, Agelaius xanthomus monensis, occurs only on Mona Island, and

the smaller adjacent Monito Island, about half-way between Puerto Rico and the

Dominican Republic.

The nominate race is on the island of Puerto Rico.

There was also a

population along the far-eastern coast of Puerto Rico, But it has presumably

vanished with no breeding recorded there since 1986.

The southwest population declined by about 80 per cent between 1975 and 1981, to

a low of 300 individuals in 1982. Subsequently, roost counts during the decade

from 1985 to 1995 showed an average annual increase of 14 per cent.

In early 1998, the total population was estimated at 1,250 individuals.

Formerly, the Yellow-shouldered Blackbird occurred in mangroves, pastures,

coconut and palm stands, cactus scrub, coastal cliffs, and rarely in woodland.

It has always been found to be most common near the coast. Many birds nest on

offshore cays.

The bird forages both on the ground and in trees, feeding on insects (especially

moths and crickets), seeds, and nectar.

Birds gather communally at feeding sites, with flocks forming in the

non-breeding season.

The breeding season is from May to September, with nests are often low in

mangrove trees, or in large deciduous trees near mangroves. On Mona Island,

nests are in crevices or on ledges on high, vertical

sea-cliffs.

A Yellow-shouldered Blackbird photographed during a FONT Puerto Rico tour.

The rare species has been seen during all 27 of the FONT tours on the

island.

22 JAMAICAN BLACKBIRD ______ Jamaica

(endemic)

Nesopsar nigerrimus

23 CUBAN (or ZAPATA) SPARROW ______

(endemic to Cuba)

Torreornis inepectata

24 SAINT LUCIA BLACK FINCH ______ Saint Lucia

(endemic)

Melanospiza richardsoni

There is a connection between the Saint

Lucia Black Finch and the

"Darwin's Finches" of the Galapagos. At one time, it was thought that

the Saint Lucia bird was one of them.

Here's the story, taken in part from the book "Far Afield in the

Caribbean" written by Mary Wickham Bond, the wife of the ornithologist

James Bond, who specialized in West Indian birds. The just-mentioned book was

published in 1971, and in the anecdote Mrs. Bond refers to her husband, Jim.

The story (of the Saint Lucia Black Finch) began in 1835 when Charles Darwin

collected his black finches in the Galapagos Islands, a group of birds peculiar

to that archipelago. His study of them occupied him for the next 15 years, and

helped lay the basis for his "Origin of the Species".

About 50 years later, the Smithsonian Institution sent out an expedition to the

Galapagos on the steamer, the "Albatross". On the way, the expedition

stopped at several islands including Saint Lucia (in the Caribbean), where a

collection of birds was bought from a local man. Among them was a black finch

that was strikingly like the Darwin's Galapagos Finch. When asked where he got

the bird, the local man waved his hand in a vague way and said "Up in the

mountains".

However, later, it was erroneously assumed that the unusual specimen had

probably been collected in the Galapagos, and was mistakenly labeled as having

come from Saint Lucia.

In 1927, before Jim (Bond) set out on his first trip to the West Indies, he

stopped at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Mr. De Witt

Miller, one of the older curators, said to him there, "If you get as far as

Saint Lucia be sure to look for Melanospiza (the genus of "the black

finch"). We're still not convinced that the our specimen was

collected there."

Jim spent 6 weeks on Saint Lucia and looked "everywhere" for the

finch, but didn't find it. However, later, during his second trip to the

Caribbean, he returned to Saint Lucia during the month of May, a better time to

find rare birds as it's the breeding season and they're in song.

That time, he did find it, collecting several, including the first females known

to science, from the mountainous country Soufriere.

On his return to New York, he (Bond) stopped in again at the American Museum. He

got the word of his find to Mr. Frank Chapman, the head of the museum's bird

department.

The Darwin's Finches, the most primitive of the Galapagos landbirds, have been,

over the years, the subject of many studies and publications by naturalists from

all over the world, including the eminent English ornithologist, David Lack. He

examined specimens of all the finches of North, South, and Central America, and

finding nothing like the Darwin's Finches among them, he decided they were a

distinct family. But he did not include in his studies the Antillean finches.

Had he done so, he would have noted how closely Melanospiza resembled the

Galapagos Finches.

The discovery by Jim (Bond) established the fact that Melanospiza was indigenous

to Saint Lucia, which strongly indicated that the Darwin's Finches and Melanospiza which invaded the Galapagos Islands and the West Indies, where they

survive (but in the West Indies only in Saint Lucia), through the lack of

competition with mainland species and the absence of significant predators.

Now, introduced mongooses and rats predate eggs, nestlings, and adults. A survey

in 1987 failed to find any large population, and noted that much suitable

habitat was unoccupied. At present, the species occurs mostly in the mountains.

25 HISPANIOLAN CROSSBILL

______ Dominican Republic

(endemic to Hispaniola)

Loxia megaplaga

The Hispaniolan Crossbill has been considered conspecific with

the White-winged or Two-barred, Crossbill. The bird, in the pine forests high in the mountains of

Hispaniola, has been there a long time, as far back as the Glacial Age in

Pleistocene times, about 85,000,000 years ago.

In that sense its history is long. In another, it's short. The bird was

discovered in the 20th Century, in 1916. Only 4 other species of birds on

Hispaniola were discovered in the 20th Century: the Least Poorwill, the LaSelle

Thrush, the Western Chat-Tanager, and the Hispaniolan Highland

Tanager, that's been known as the White-winged Warbler. (All of these species are included in this listing or rare

birds in the Caribbean.)

Most birds, of course, not just on Hispaniola, but throughout the World, were

known to science before the beginning of the 20th Century.

The Hispaniolan Crossbill has a very small population (with at least 4

subpopulations). Numbers fluctuate naturally.

In the Dominican Republic, the species was not recorded from about 1930 to 1970.

In that country, now, it is most often found in the Sierra de Baoruco mountains,

with occasional records in the Cordillera Central.

It is believed that numbers declined during much of the 20th Century due to

habitat loss, but by 1980 the bird was thought to be recovering. A population of

less than 1,000 individuals was estimated in 1994, but, as noted, numbers

fluctuate, depending on food supply.

In Haiti, the bird has been known from the mountainous areas of Massifs de la

Selle and de la Hotte, and a flock of 30 was noted in January 2000 at La Visite.

Interestingly, away from Hispaniola, several birds were found in the Blue

Mountains of Jamaica in the early 1970's, but never subsequently. Were they

blown there by a hurricane? So many birds of the Caribbean have to cope with

such a strong force of nature. And birds with fragile, low populations can

therefore, at times, be all the more in

jeopardy.

26 RED SISKIN ______ an

introduced species in Puerto Rico

Sporagra

(formerly Carduelis) cucullata

The population of the Red Siskin in Puerto Rico, from escaped cage

birds probably in the 1930s, has undergone lately a marked decline, and there

have been few recent records.

The following relates to the Red Siskin where it is native, and very rare, in northern South

America:

The Red Siskin, or the "Cardenalito"

as it's known in Spanish, is a rare and endangered species. The bird has been

known to occur locally in northern Colombia and northern Venezuela, and nearby

Guyana.

It was very good news for the species when, in 2003, a population of several

thousand birds was discovered in southern Guyana, about a thousand kilometers

from any previously known population. Otherwise, the global population of the

species in the wild has been estimated to be from 600 to 6,000 pairs.

In the early 20th Century, the Red Siskin was common in the foothills of

northern Venezuela, but later in the 1900s it became extremely rare there in a

fragmented range.

The preferred habitats of the Red Siskin are open country, forest edges,

and grasslands with trees or shrubs.

Red Siskins are highly gregarious. When they were more numerous, they

formed semi-nomadic flocks.

The main reason for the decline of the Red Siskin has been massive

illegal trapping for the cage bird trade. Being an attractive finch with a

pleasant song is against it, and its unique coloration for a small finch that

has enabled it to be used for interbreeding with domesticated Canaries to

produce varieties with red in the plumage.

27 EASTERN CHAT-TANAGER ______ Dominican

Republic (endemic)

Calyptophilus frugivorus

The Eastern Chat-Tanager was seen during the

FONT Dominican Republic Tour in February 2012, in the mountains of the

Cordillera Central.

That subspecies, Calyptophilus frugivorus neibei, occurs uncommonly and

locally in the Cordillera Central and Sierra de Neiba mountains in the central

Dominican Republic.

Two other subspecies of the Eastern Chat-Tanager have occurred, on the Semana Peninsula

in the northeastern Dominican Republic and on Gonave Island in Haiti, but

neither of them have not been found in decades. Those subspecies are

respectively, C. f. frugivorus &

C. f. abbotti.

In the 2000 edition of Birdlife International's "Threatened Birds of the

World" it was written the "much needed redefinition of the taxonomic

status of the Chat-Tanager would almost certainly result in a significant change

of the bird's 'vulnerable' classification". Since then (and reflected

here), some taxonomic revision has been done, and the Eastern Chat-Tanager

has been classified as "endangered", while the Western Chat-Tanager remains

"vulnerable".

In the book, "Birds of the Dominican Republic and Haiti",

published in 2006, the Eastern Chat-Tanager was categorized as

"critically endangered".

Birdlife International, still as of 2012, categorized the species as "vulnerable",

as they question the split of the Western Chat-Tanager from the Eastern

Chat-Tanager, and collectively they consider the bird as the "Chat-Tanager".

In our view, we note the Western Chat-Tanager as "vulnerable"

(below), and the Eastern Chat-Tanager here as at least "endangered",

although the assessment of the authors of the 2006 field guide may be

correct.

The nominate of the Eastern Chat-Tanager was described back in the 19th Century,

in 1883.

The race on Gonave Island was described in 1924.

And, most recently,

the subspecies that is still known to exist today, C. f. neibei, was described

only as recently as 1977.

See also the text that follows with the WESTERN CHAT-TANAGER

(among the

species in the "vulnerable"

category)

Species in the Caribbean classified as VULNERABLE:

28 WEST INDIAN WHISTLING DUCK

______ Barbuda, Cayman Islands, Dominican Republic,

Jamaica, Puerto Rico

Dendrocygna arborea

The West Indian Whistling Duck occurs only on various West Indian

islands, where its range is extremely fragmented.

Whereas its remaining habitat has been declining, and the West Indian

Whistling Duck has disappeared from some sites where it has been, there

seems recently to have been an overall slight increase in the bird's population.

The duck is generally crepuscular or nocturnal, and often

secretive.

During FONT Caribbean Tours, the West Indian Whistling Duck has been seen on 5 islands

as noted above.

Some recent information about the approximate, or estimated populations of the West

Indian Whistling Duck on various islands is as follows:

Barbuda: 50 birds (with maybe 500 in nearby Antigua)

Cayman Islands: from 800 to 1,200 birds

Dominican Republic: apparently 6 populations, the number of birds unknown

Jamaica: 500 birds

Puerto Rico: perhaps 100 birds

At least 1,500 birds are said to exist in the Bahamas.

On January 6, 2001, a pair of

West Indian Whistling Ducks with 3 chicks marked the first nesting record

for the species on Abaco Island in the Bahamas.

A West Indian Whistling Duck

photographed during a FONT tour

in the Dominican Republic

(photo by Marie Gardner)

29 RING-TAILED PIGEON ______ Jamaica

(endemic)

Patagioenas

(formerly

Columba)

caribaea

30 WHITE-FRONTED QUAIL-DOVE ______ Dominican Republic

(endemic)

Geotrygon leucometopius

The White-fronted Quail-Dove was considered conspecific with the Gray-headed Quail-Dove (below).

31 GRAY-HEADED QUAIL-DOVE ______

(endemic to Cuba)

Geotrygon caniceps

32

HISPANIOLAN PARAKEET

______ Dominican Republic

(endemic to Hispaniola)

Aratinga chloroptera

The Hispaniolan Parakeet has a small and fragmented range and population, which

continues to decline due to persecution.

Overall on the island of Hispaniola, the bird is rare with isolated populations

in the Dominican Republic, in the Cordillera Central, the Sierra de Baoruco, and

in some neighborhoods on the western side of the city of Santo Domingo.

The

current status of the bird in Haiti is unclear. It has been suggested that it is

extinct there, there have been claims that it is in the Massif de la Selle and

la Citadelle area of the Massif du Nord. (It should be noted that the

Jamaican

(formerly Olive-throated) Parakeet occurs now in western Hispaniola.)

A race of the Hispaniolan Parakeet, Aratinga chloroptera maugei, has become

extinct. It formerly occurred on Mona Island, Puerto Rico (about halfway between

the Dominican Republic and the island of Puerto Rico).

There is a feral population of the Hispaniolan Parakeet in Puerto Rico, and

possibly on the Lesser Antillean island of Guadeloupe.

A Hispaniolan Parakeet photographed during a FONT

tour

(photo by Marie Gardner)

33 HISPANIOLAN AMAZON

(or

Hispaniolan Parrot) ______ Dominican Republic

(endemic to Hispaniola)

Amazona ventralis

The Hispaniolan Amazon (or Hispaniolan Parrot) was common on the island of Hispaniola, but it declined

seriously during the 20th Century. By the 1930's. it was mainly restricted to

the mountains in the central and southwestern Dominican Republic and in western

Haiti, where it still remains locally common. Recent evidence, however, has

suggested that there has been, as of late, a rapid population reduction. But the

current extent of the decline, and the present population of the species is

unclear.

The bird inhabits a variety of wooded habitats, from arid palm-savannas to pine

and montane humid forests, occurring as high as 1500 meters (4500 feet) above

sea level. It frequently forages in cultivated lands, such as banana plantations

and corn fields. Nesting is known to take place from February to May, maybe

later,

Introduced Hispaniolan Amazons are established in Puerto Rico, and in the Virgin

Islands on St. Croix and St, Thomas. The population in Puerto Rico is several

hundred birds, and is apparently increasing.

34 YELLOW-BILLED AMAZON ______ Jamaica

(endemic)

Amazona collaria

Yellow-billed Amazon

(photo by Suzanne Bradley)

35 BLACK-BILLED AMAZON

______

Jamaica

(endemic)

Amazona agilis

36 RED-NECKED AMAZON (or Red-necked

Parrot) (the "Jaco")

______ Dominica

(endemic)

Amazona arausiaca

During recent decades, the Red-necked Amazon, or Red-necked Parrot, has done a bit better than the

other amazon that inhabits the same area of Dominica, the Imperial Amazon (see

above, under "endangered").

The population of the Red-necked Amazon is a few hundred birds.

Both the Red-necked and Imperial Amazons, however, are quite vulnerable to

disasters such a direct hit by a powerful hurricane. Actually, the number of Red-necked

Amazons was halved by such events in 1979 and 1980.

37 SAINT LUCIA AMAZON

(the "Jacquot")

______ Saint Lucia (endemic)

Amazona versicolor

The Saint Lucia Amazon, when seen well, is a beautiful parrot. It is an

overall green bird, with a iridescent blue face and a scalloped black and red

breast. In 1950, its population was believed to be about 1,000 birds. A survey

in 1978 estimated that only about 100 birds continued to exist. During those 25

or so years, suitable habitat reduced rapidly.

After the 1970's, diligent conservation efforts saved the species from

extinction. A survey in 1996 estimated the wild population to be between 350 and

500 individuals, and it noted some slight range expansion.

However, the human population on the island of Saint Lucia is growing at a

considerable rate, and there is increasing pressure on the forest resulting

lately in some habitat loss. So, the area of apparently suitable habitat

(unoccupied by parrots) may now be decreasing, and if this begins to affect the

suitable habitat that is currently occupied by parrots, the status of the bird

would need to be changed from "vulnerable" to "endangered",

as the species does have such a small range in which an appropriate habitat is

required.

38 SAINT VINCENT AMAZON ______ Saint Vincent

(endemic)

Amazona guildingii

The Saint Vincent Amazon is really quite a bird. It occurs in two general color

schemes, brownish or greenish. Both are striking birds with white on their

heads, blue on their faces, and bright yellow in their wings and tails.

In the early 1970's, there were an estimated 1,000 of these birds. By the late

1980's, the total population was said to be about half of that.

A Saint Vincent Amazon in the wild,

photographed during the Dec 2007 FONT Tour in the Lesser Antilles.

(photo by Marie Gardner)

39 YELLOW-SHOULDERED AMAZON ______

in the Netherlands Antilles (and the coast & offshore islands of

Venezuela)

Amazona barbadensis

In the Netherlands Antilles, the Yellow-shouldered Amazon occurs

mostly on the island of Bonaire where in 2012 there were said to be over

600 birds.

On Curacao, there have been modern-day reports of parrots since 1988.

Historically, there was a parrot population on Curacao in the 18th century.

Amazona barbadensis formerly occurred

on Aruba, but it has been extirpated on that island.

40 FERNANDINA'S FLICKER ______

(endemic to

Cuba)

Colaptes fernandinae

41 WHITE-NECKED CROW

______ Dominican Republic (now

endemic to Hispaniola)

Corvus leucognaphalus

The White-necked Crow is now endemic to Hispaniola. It formerly occurred on Puerto

Rico, bur it was last recorded there

in 1963.

A White-necked Crow photographed during a FONT tour

(photo by Marie Gardner)

42 GOLDEN SWALLOW ______

Dominican Republic (now seemingly endemic

to Hispaniola)

Tachycineta euchrysea sclateri

The endemic subspecies of the Golden Swallow on the island of Hispaniola,

Tachycineta euchrysea sclateri, has a small, fragmented, and declining

population. It may now be that the population on Hispaniola is an endemic

species, as the nominate subspecies in Jamaica has not been recorded there in

years.

In Jamaica, the Golden Swallow has been (or was) very rare and local, where it

has been observed from the Cockpit Country east across the central highlands to

the Blue Mountains. The Jamaican population was said to be common in the 19th

Century.

In Hispaniola, it occurs in the Cordillera Central and the Sierra de Baoruco in

the Dominican Republic, and in the Massif de la Selle in Haiti.

Overall, the species suffered a massive decline during much of the 20th Century.

The Golden Swallow in Hispaniola favors montane humid and pine forests, from

about 800 to 2,000 meters (2,400 to 6,000 feet) above sea level. Nests are in

old woodpecker and other holes in dead pines, and have also been noted in caves,

boulders in an old bauxite mine, and in the eaves of buildings. It flies about,

either singly or in small groups, feeding on small insects.

The common English name, Golden Swallow, comes from the sheen on its back, when

the bird is seen in good sunlight from above (sometimes hard to do with a

swallow)

43 FOREST THRUSH ______ Dominica

Turdus

(formerly

Cichlherminia)

iherminieri dominicensis

The Forest Thrush has 4 subspecies. In

addition to the subspecies endemic to the island of Dominica, there are other

endemic subspecies on the islands of Guadeloupe and Montserrat, and possibly

still on Saint Lucia, where, if it still occurs, it is very rare.

Throughout its range, this species has declined significantly in recent years,

due in part to deforestation and introduced predators. The bird can be

exceedingly shy where it has been hunted (another factor in its decline).

In Montserrat, its population was reduced by two-thirds in 1995-1997 due to

effects from a major volcanic eruption, but since then, on that island, there

has been an increase. In December 1999, on Montserrat, the population was

estimated to be just over 3,000 birds.

Threats, throughout its range, have been brood-parasitism by Shiny Cowbirds and

competition with the Spectacled (formerly Bare-eyed) Thrush.

On the French island of Guadeloupe, the Forest Thrush still continues to be

legally hunted. On Dominica, it occurs in the Morne Diablotin National Park, and

in other similar forested locations.

On Saint Lucia, the bird is said to have formerly gathered in large numbers in

autumn to feed on berries.

44 BICKNELL'S THRUSH

______

Dominican Republic

Catharus bicknelli

The wintering range of the Bicknell's Thrush is restricted to the

Greater Antilles of the West Indies, on the islands of Hispaniola, Cuba,

Jamaica, and Puerto Rico.

However, most, by far, winter in the Dominican Republic on Hispaniola.

The Bicknell's Thrush, in its wintering territory, is typically shy and

wary. It searches for invertebrates and fruits on the ground or in the

sub-canopy of moist broadleaf forest, or broadleaf forest with few pines mixed

in. The bird prefers dense understory.

Surveys conducted in the 1990s in the Dominican Republic found the following

regarding the Bicknell's Thrush occurring as a seasonal non-breeding

resident:

75 per cent in wet and mesic broadleaf forests

19 per cent in mixed pine/broadleaf forests

6 per cent in pine-dominated forests.

Birds were found at all elevations from sea level to 6,600 feet above sea level.

Most, that is 62 per cent, were in primary montane forests higher that 3,000

feet in elevation.

In its migration, the Bicknell's Thrush can be found at some

lowland localities in the Dominican Republic.

During surveys in the Dominican Republic in the 1990s & the early 2000s,

places in high elevations where the Bicknell's Thrush was found included:

Sierras de Bahoruco, Neiba, and Martin Garcia, and the Cordilleras Central,

Septentrional, and Oriental. It is most common in the Sierra de Bahoruco and the

Cordillera Central.

Other places included the Los Haitises National Park and less so in the Del Este

National Park.

The surveys seem to have found some sexual segregation among birds wintering in

the Dominican Republic with males mostly in undisturbed montane forests, while

females and birds of the year in younger, or more disturbed

forests.

The arrival of Bicknell's Thrushes in the Dominican Republic is thought

to be in late October and early November.

The birds probably start their northward spring migration in early to

mid-April.

45 ELFIN WOODS WARBLER ______ Puerto Rico

(endemic)

Setophaga

(formerly Dendroica) angelae

It was as recently as 1971 that the Elfin Woods Warbler was discovered. Endemic

to Puerto Rico, it is uncommon and local in 4 disjunct areas of the island. In

the east, it is in the Sierra de Luquillo (in the Caribbean National Forest) and

in the Sierra de Cayey (in the Carite Forest). In the west, in the Cordillera

Central (in the Maricao & Toro Negro Forests). The total population, at

these localities where the bird is known, has been estimated at no more than 300

pairs.

As indicated by its name, the bird inhabits elfin, or montane dwarf, forest on

ridges and summits, and montane wet forest. Preferred areas have a dense canopy

with vines, high sub-canopy and sparse understory. Although it has been found in

secondary habitats, it occurs most in undisturbed forest. Breeding takes place

from March to June.

By the late 1940's, the natural vegetation of Puerto Rico had been reduced to

about 6 per cent of the island's land surface, but a later regeneration of

forest increased the figure to about 30 per cent in the early 1980's.

46 CERULEAN WARBLER ______ a

migrant in the West Indies

Setophaga (formerly Dendroica) cerulea

47 HISPANIOLAN HIGHLAND TANAGER

(has been called White-winged Warbler) ______

Dominican Republic

(endemic)

Xenoligea montana

The Hispaniolan Highlands Tanager (that has also been known as the White-winged

Warbler) was one of

the four Hispaniolan birds discovered in the 20th Century.

When it was

described, in 1917, it was given the scientific name Microlgea

montana. It

occurs high in the "montanas" (or mountains). In 1967, the bird became

the single member of its genus, and the new scientific name given to it at that

time was Xenoligea montana.

48 WESTERN CHAT-TANAGER ______ Dominican Republic

(endemic to Hispaniola)

Calyptophilus tertius

The bird currently called the Western Chat-Tanager has been considered a

subspecies of the Eastern Chat-Tanager, Calyptophilus frugivorus, but

it is now said by some to be a distinct species.

The Western Chat-Tanager, with a length of 8 inches, is just over an inch larger

than the Eastern Chat-Tanager at 6.75 inches, and it lacks the bare yellow

eye-ring of the Eastern Chat-Tanager. The voices of the two Chat-Tanagers are

noticeably different.

The local name of the Western Chat-Tanager is "El Chirri". That of the

Eastern Chat-Tanager (the race in the central Dominican Republic) is "El

Patico".

The Western Chat-Tanager, Calyptophilus tertius, occurs in southwestern

Hispaniola in Haiti and the adjacent Dominican Republic, where it is local in

the Sierra de Baoruco mountains.

The Eastern Chat-Tanager, Calyptophilus frugivorus neibei, occurs uncommonly and

locally in the Cordillera Central and Sierra de Neiba mountains in the central

Dominican Republic.

Two other subspecies have occurred, on the Semana Peninsula

in the northeastern Dominican Republic and on Gonave Island in Haiti, but

neither of them have not been found in decades. Those subspecies are

respectively, C. f. frugivorus &

C. f. abbotti.

In the 2000 edition of Birdlife International's "Threatened Birds of the

World" it was written the "much needed redefinition of the taxonomic

status of the Chat-Tanager would almost certainly result in a significant change

of the bird's 'vulnerable' classification". Since then (and reflected

here), some taxonomic revision has been done, and the Eastern Chat-Tanager

has been classified as "endangered", while the Western Chat-Tanager remains

"vulnerable".

The nominate of the Eastern Chat-Tanager was described back in the 19th Century,

in 1883.

The race on Gonave Island was described in 1924.

And, most recently,

the subspecies that is still known to exist today, C. f. neibei, was described

only as recently as 1977.

What is now the Western Chat-Tanager was described in 1929 (first as a

subspecies), making it now the last of the birds of the Dominican Republic (at

least, to date) to be described.

As noted here elsewhere, 4 other species of

birds in the Dominican Republic were described in the 20th Century: the Hispaniolan

Crossbill in 1916, the Least Poorwill and the Hispaniolan Highlands

Tanager in 1917, and the La Selle Thrush in 1927. A second subspecies of the last

of these, the thrush, was found in the Central Mountains of the Dominican

Republic as recently as 1986.

The speciation of the two Chat-Tanagers is said to have most likely occurred

when present-day Hispaniola consisted of two separate islands.

The Chat-Tanagers are largely terrestrial in broadleaf forests and dense

thickets, and they particularly favor ravines. The two species, C. tertius &

C. frugivorus neibei, are primarily montane. They feed chiefly, near the ground,

on invertebrates, rather than on fruits as implied by the scientific name "frugivorus".

Even though the Western Chat-Tanager is one of the finest of Hispaniola's avian

songsters, the bird can be notoriously hard to see, being an adept skulker.

That

notwithstanding, during the FONT Dominican Republic tour in April 2008, the Western

Chat-Tanager was both heard & seen very well - so much so, that it

was voted the "top bird" of the tour! (And it might well be noted that

the bird was seen well because of its own activity, and not due to a response to

a tape).

Apparently, in the remote area where we were, the birds had a nest near

the road. One of them, at least, was seen repeatedly flying across the road, and

perching, not high, on a nearby branch. So many times, in the past, we only had

a glimpse of the bird. After all, there is a reason why it was described as late

as

1929.

Species in the Caribbean classified as NEAR-THREATENED:

49 BLACK RAIL ______

Laterallus jamaicensis

50 CARIBBEAN COOT ______ Dominican Republic,

Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Saint Lucia

Fulica caribaea

The Caribbean Coot has been said by some to be conspecific with the American Coot,

F. americana.

51 PIPING PLOVER ______

Charadrius melodus

52 BUFF-BREASTED SANDPIPER ______ a southbound migrant in

the West Indies, in the late-summer & early-fall

Tryngites subruficollis

53 WHITE-CROWNED PIGEON ______ Antigua,

Cayman Islands, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Puerto Rico

Patagioenas (formerly Columba)

leucocephala

54 PLAIN PIGEON ______ Dominican Republic,

Puerto Rico

Patagioenas (formerly Columba) inornata

55 CRESTED QUAIL-DOVE (the

"Mountain Witch")

______ Jamaica (endemic)

Geotrygon versicolor

56 ROSE-THROATED AMAZON

______ Cayman Islands

Amazona leucocephala

This species has various names on different Caribbean islands.

It's known as the Bahama, the Cuban

and the Cayman Islands Amazon, or Parrot

There are 5 subspecies, 2 in Cuba, 1 in the Bahamas, and 2 in the Caymans:

A. l. caymanensis, ______ Grand Cayman, in the Cayman Islands

(endemic

subspecies)

A. 1. hesterna, ______ Cayman Brac Is., in the Cayman

Islands (endemic subspecies)

The Rose-throated Amazon, or the Cayman Islands Amazon,

a species always seen during FONT tours on those islands.

57 LEAST POORWILL ______

Dominican Republic

(endemic)

Siphonorhis brewsteri

The Least Poorwill had, for a while, a scanty history, after the first specimen

was collected in 1917. At that time, the small nightjar, that has also been

called the Least Pauraque, was given the scientific name Microsiphonorhis

brewsteri. The genus was changed in 1928 to Siphonorhis.

From that year, until 1969, there were very few, if any, reports of this bird,

that locally is called "El Torico".

The nice thing is that today this species of Siphonorhis can still be found (as

it is during our tours). The only other member of the genus, Siphonorhis

americana, the Jamaican Poorwill (or "Jamaican Pauraque"), is now

believed to be extinct.

The Least Poorwill is a small bird, with a length as little as just over 6

inches. In western North America, the Common Poorwill is about an inch to two

inches longer.

And, as a frame of reference, the familiar American Robin has a

length of about 10 inches.

Reasons why this small nightjar escaped detection for almost 50 years in the

20th Century are that the bird is entirely nocturnal, and that it lives in dense

vegetation in areas of cactus and thorn scrub where, in general, not many people

penetrate. Its distribution is local. Where it occurs, it may be relatively

common, but overall it is not.

We have found that, during FONT tours, at an appropriate place, the Least

Poorwill can begin calling at dusk, and that when (if) it responds to a tape, it

can fly by quickly, close to the ground, like a 6-inch dart.

It's written that the downy young of the Least Poorwill looks like a fluffy ball

of white cotton, and that it appears to mimic a round whitish cactus which grows

where the bird nests. Actually, the first nestling was discovered by a botanist

collecting cacti. The bird was thought to be a cactus until it moved.

58 BEE HUMMINGBIRD ______ (endemic to Cuba)

Mellisvea helenae

The Bee Hummingbird is said to be the smallest of all

birds.

59 HISPANIOLAN TROGON

______ Dominican Republic

(endemic to Hispaniola)

Priotelus roseigaster

A Hispaniolan Trogon photographed during a FONT tour in the Dominican Republic.

The species has been found during all 19 FONT tours on that island.

60 GUADELOUPE WOODPECKER

______ Guadeloupe

(endemic)

Melanerpes herminieri

Geographically Isolated, from away from any other woodpecker, the Guadeloupe

Woodpecker is endemic to that one island in the Lesser Antilles.

Guadeloupe is an overseas prefect of France. It has 2 senators and 3 deputies in

the French parliament in Paris. The license plates on the mostly small vehicles

are as those in France. The money is as that in France, the Euro. Of the

thousands of tourists who visit Guadeloupe each year, mostly for its beaches,

far and away the most are from France.

So it is not surprising that the Guadeloupe Woodpecker has a French name,

the "Tapeur". It is from "taper" meaning "to

tap", or "to strike, bang, or beat".

Of the more than 200 species of woodpeckers in the world, there are things about

the "Tapeur" that set it apart from the others.

It has a reddish-purple breast and belly, but often the bird appears all-black.

In flight, the bird does not undulate as woodpeckers normally do.

Its call is also distinctively its own, a loud "ch-arrgh" given by

birds in the forest to maintain contact with each other.

Oddly, the closest woodpecker to it, in terms of appearance and structure, is

the Lewis' Woodpecker of western North America. It is in the same genus

as the Lewis', Melanerpes.

But the Guadeloupe Woodpecker is so geographically isolated from others

in the woodpecker family. There are also Melanerpes

woodpeckers in the Greater Antilles and in Central and South America, but

there is no other woodpecker of any kind in the Lesser Antilles.

The "Tapeur" is a rather shy, and often

inconspicuous bird of the dense forest and other wooded habitats.

It occurs below 1,000 feet above sea level.

It is estimated that its population may be 10,000 pairs.

The bird does not "flycatch". Its diet of insects is taken in dead

wood.

A particularly interesting aspect of Melanerpes

hermionieri, the Guadeloupe Woodpecker, is that the length

of the male's bill is 20 per cent longer that that of the female.

During our FONT tours in Guadeloupe, we have been fortunate to see pairs,

together, in bare trees, and that notable difference in bill length could easily

be seen.

61 HISPANIOLAN PALM CROW ______ Dominican Republic

(now a subspecies endemic to Hispaniola)

Corvus p. palmarum

The Hispaniolan Palm Crow has been split from the "Cuban

Pam Crow", Corvus palmarum minutus,

but now the two are considered conspecific.

62 BLUE MOUNTAIN VIREO ______ Jamaica

(endemic)

Vireo osburni

63 CUBAN SOLITAIRE ______ (endemic to Cuba)

Myadestes elisabeth

64 GOLDEN-WINGED WARBLER ______

a migrant in the West Indies

![]()

Regarding SUBSPECIES:

Some Subspecies

in the Caribbean classified as ENDANGERED:

SHARP-SHINNED HAWK ______ Puerto Rico

(endemic)

Accipiter striatus venator

The subspecies of the Sharp-shinned Hawk

in Puerto Rico

BROAD-WINGED HAWK ______ Antigua

(endemic)

Buteo platypterus insulicola

There are 5 subspecies of the Broad-winged Hawk on West Indian islands.

All of them are residents, never coming in contact with those of the same

species in eastern North America, Buteo p.

platypterus.

The resident Caribbean subspecies occur in Cuba, Puerto Rico (below), and

in the Lesser Antilles with B. p. rivierei on

Dominica, Martinique, and St, Lucia, and B. p.

antillarum on St. Vincent, Grenada, Barbados, and Tobago.

The fifth Caribbean subspecies, Buteo platypterus

insulicola, on Antigua, has the smallest range of any of the

subspecies, being endemic to just that one small island.

The bird on Antigua is said to be smaller and lighter than any other subspecies

of Broad-winged Hawk.

The subspecies of the Broad-winged Hawk on Antigua is the only bird

endemic to that island.

STYGIAN OWL ______ Dominican

Republic

Asio stygius noctipetens

The subspecies of the Stygian Owl on Hispaniola,

A. s. noctipetens, is said to be

smaller and with whiter markings than other subspecies in Central and South

America.

On Hispaniola, the Stygian Owl is a very rare breeding resident in dense

deciduous and pine forests in remote areas.

In recent years, all of the localities where it has been found are in remote old

forests, sometimes near caves or in wooded ravines, and not near human dwellings

or in second-growth habitats.

Since the mid-1980s, the Stygian Owl has been found sporadically in the

pine forests of the Cordillera Central, on the Samana Peninsula, in the Los

Haitises National Park, and in the Sierra de Bahoruco. It also occurs on the Ile

de Gonave.

"SAINT LUCIA" RUFOUS NIGHTJAR ______ Saint Lucia

(endemic)

Caprimulgus rufus otiosus

SHARP-SHINNED HAWK ______ Dominican Republic

(endemic)

Accipiter s. striatus

BROAD-WINGED HAWK ______ Puerto Rico

(endemic)

Buteo platypterus brunnescens

LIMPKIN ______ Dominican Republic

(where

now endemic, as it has been extirpated in Puerto Rico)

Aramus guarauna elucus

DOUBLE-STRIPED THICK-KNEE ______ Dominican

Republic

Burhinus bistriatus

SNOWY PLOVER ______ Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico

Charadrius alexandrinus nivosus

A Snowy Plover photographed during a FONT tour

in the Dominican Republic

(photo by Marie Gardner)

ROSEATE TERN ______ Dominican Republic, Puerto

Rico, St. Lucia

Sterna d. dougallii

"SAINT LUCIA WREN" ______ Saint Lucia

(endemic)

Troglodytes aedon mesoleucus

The subspecies of the House Wren on nearby Martinique has been

extirpated.

"SAINT VINCENT WREN" ______ Saint Vincent

(endemic)

Troglodytes aedon musicus

![]()

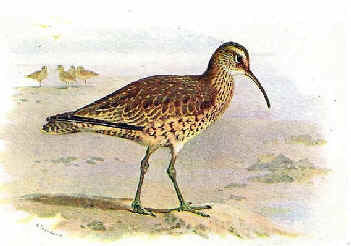

A painting of an Eskimo Curlew by Archibald Thorbum

Another name for the Eskimo Curlew was the "Doe-bird",

sometimes spelled "Dough-bird". That name was due to the bird's

acquiring of fatness for its long journey south.

As North America was being settled by the Europeans, the Eskimo Curlew

was one of the most abundant birds on the continent.

It bred on the Barren Grounds of northern Canada. It wintered in

far-southern South America. It migrated in between.

It was said, during its southbound migration, to have visited Newfoundland

"in millions" darkening the sky.

John James Audubon, Elliot Coues, and other ornithologists of the early 1800s

told of immense flights.

In the Prairie States, the numbers of Eskimo Curlews so resembled

the tremendous flights of Passenger Pigeons that they were called

"Prairie Pigeons".

A single flock alighting in Nebraska was said to have covered 40 to 50

acres of ground.

The Eskimo Curlew migrated south in August southeast to Labrador and

Newfoundland, where they fed on "curlew berries" (Empetrum

nigrum) and snails, gaining the weight needed for their long journey out over

the sea to South America.

Easterly storms, such as hurricanes that time of year, sometimes brought them

onto the coasts of New England and Long Island, New York.

They often touched down on Lesser Antillean islands, such as Barbados,

before continuing on to to the coast of Brazil, and then further to Argentina.

During their northbound spring route, after crossing the Gulf of Mexico, they

arrived in March in southern Texas, and then continued up the western

Mississippi Valley, and thence further north to where they would nest.

But from being abundant, the status of the Eskimo Curlew

in the 19th Century certainly changed.

Incredibly, the Eskimo Curlew was not seen anywhere at its known breeding

grounds for years after 1865.

Just over a century later, in 1987, a small nesting colony was said to be found

in the Canadian Arctic, that was maybe the last.

The last breeding grounds of the Eskimo Curlew in northern Canada are

said to have been in either Ungava or Franklin.

The last Eskimo Curlews were either seen or shot at these places as

follows:

in Illinois in 1872

in Ontario in 1873

in Ohio in 1878

in Arkansas and Michigan in 1883

in South Dakota and Oklahoma in 1884

in Minnesota in 1885

in Louisiana, Pennsylvania, and Newfoundland in 1889

in Indiana in 1890

in Iowa in 1893

in Prince Edward Island in 1901

in Kansas, Missouri, and Nova Scotia in 1902

in Quebec in 1906 (fair-sized flocks in the fall were in Quebec

until 1891)

in Wisconsin in 1912

in Maryland, and Bermuda in 1913 (fair-sized flocks were in Bermuda

until 1874)

in Massachusetts in 1916 (fair-sized flocks were in Massachusetts

until 1883)

in Nebraska in 1926 (there was a more-recent report in Nebraska in

1987)

in Maine in 1929 (fair-sized flocks were in Maine until

1879)

in Labrador and Long Island, New York in 1932 (fair-sized flocks

in the fall were in Labrador until 1892)

in South Carolina in 1956

in New Jersey in 1959

in the Bahamas in 1963

in Barbados in the Lesser Antilles in 1964, when one was shot.

No spring migrant was seen anywhere other than Texas since 1926.

Along the Gulf coast of Texas, the last confirmed sighting, with a

photograph, was at Galveston in 1962. A flock of 23 birds was reported there in

1981.

There were additional, but unconfirmed records of Eskimo Curlews:

in Texas and Canada in 1987 (the Canadian "breeding

site" noted above), in Nova Scotia in 2006, and in Argentina

in 1990.

The last Eskimo Curlews seen and confirmed at wintering grounds in South

America, were in Argentina back in n 1939.

With prevailing westerlies or strong storms, Eskimo Curlews were at times

seen across the Atlantic Ocean:

Sighted or shot:

in England in 1852 (2 birds) and 1887.

in Scotland in 1855, 1878, 1880.

in Ireland in 1870.

CUBAN, or

HISPANIOLAN RED, MACAW

______

Cuba

(from where specimens were

obtained)

& Hispaniola

(no specimens)

Ara tricolor

The last known occurrence of a Cuban (or Hispaniolan) Red

Macaw, Ara

tricolor, was when a single wild bird was shot in the area of the Zapata Swamp

in Cuba in 1864. Probably a few birds survived beyond that, until about 1885.

Cory, at about that time, wrote: "Dr. Gundlach writes me that he believes

it still occurs in the swamps of southern Cuba".

A few years earlier,

Gundlach noted that in 1849 it could easily be found.

In the 1850s, the last

flock came regularly to feed in a small group of trees at Zarabanda, also in the

Zapata Swamp area of Cuba.

The Cuban (or Hispaniolan) Red Macaw was similar to the

Scarlet Macaw of Central

& South America, but smaller (about 20 inches in length). It had a red

breast and brow, a yellow crown and neck, dark blue wings, and a long tail that

was blue above and red below.

The bird nested in holes and clefts in palm trees, and favored those palms and

the flowering Melia trees for their diet of fruit, seeds, sprouts, and buds.

It's been noted that on occasion the Cuban people killed the macaws for food,

and that they captured them, usually in their nests, to be pets.

The Hispaniolan, or Cuban Red Macaw,

now extinct

There is historical reference to a red macaw, also, on the Caribbean island of

Hispaniola (now thought to be the same species as in Cuba).

In a study in 1985, it was concluded that the origins of Ara tricolor

were on Hispaniola,

not Cuba. On the basis of old descriptions, it's said that the macaws on

Hispaniola could have been a separate subspecies, with a smaller bill, and some

minor plumage differences such as a white forehead, rather than red as on the

Cuban bird.

No specimens now exist from Hispaniola, but there are still, throughout the

world, 19 specimens of the macaws from Cuba, in various museums including those

in: Havana, New York, Washington, Cambridge, Mass., London, Liverpool, Paris,

Vienna, Berlin, Dresden, Leyden, Stockholm, and Tring.

This species of macaw may also have occurred, historically, on Jamaica, as

"a red macaw" was reportedly shot there in 1765. Unfortunately, that

skin was lost. That bird is the first of those listed below.

There seems also to have been some other such macaws, without remaining

evidence, on some other West Indian islands: Guadeloupe, St. Croix, and St.

Vincent.

"Yellow-headed Macaw" ______ Jamaica (endemic?, as either a subspecies

or a species )

Ara (tricolor) gossei (last known

in 1765)

Green-and-Yellow Macaw ______

Jamaica (e)

Ara erythrocephala (last known in

1842)

Dominican Macaw ______

Dominica (e)

Ara atwoodi (last known in 1800)

Labat's Parakeet (or Conure) ______

Guadeloupe (e)

Aratinga labati (last known in

1722)

Guadeloupe Amazon (or Parrot) ______

Guadeloupe (e)

Amazona violacea (last known in

1750)

Martinique Amazon (or Parrot) ______

Martinique (e)

Amazona martinica (last known

1750)

JAMAICAN POORWILL ______ Jamaica (e)

Siphonorhis americanus

(last known in 1859)

Siphonorhis americanus has also been called

Jamaican Pauraque.

BRACE'S HUMMINGBIRD ______ Bahamas

Chlorostilbon bracei

The Brace's Hummingbird is known only from one specimen collected in

1877.

"CUBAN IVORY-BILLED WOODPECKER" ______

Cuba

Campephilus (principalis) bairdii (endemic to Cuba)

Recent DNA evidence (published in 2006) indicates that what has been said

to be a subspecies of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in Cuba, Campephilus (principalis)

bairdii, is (was) not.

First described in 1863 as a separate species, the Cuban bird has been shown to

be a species more closely related to the Imperial Woodpecker of Mexico than to

the Ivory-billed Woodpecker of the southeastern United States.

By that year (2006), it may well be that all 3 of those woodpeckers had become

extinct.

As to habitat, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker of the US has been (or was) in mature

lowland hardwood forest, usually by water. The Cuban Ivory-billed Woodpecker has

been (was) in mature lowland hardwood and hill pine forests. The Imperial

Woodpecker in Mexico occurred in pine forests in hills and mountains.

In recent study, dating analyses reveal that the American & the Cuban Ivory-billed

Woodpeckers and the Imperial Woodpecker diverged sometime in the

mid-Pleistocene. A sea-level difference at that time of more than 30 meters (90

feet) would have increased the size of the Yucatan Peninsula and reduced the

current distance between the Yucatan Peninsula and Cuba, and thus, could

possibly, have favored colonization of Cuba by a woodpecker presumably averse to

flying over water.

GRAND CAYMAN THRUSH ______ Cayman Islands (on Grand Cayman Is.)

(e)

Turdus ravidus

BACHMAN'S WARBLER ______ Cuba

Vermivora bachmanii

The Bachman's Warbler was a winter visitor in Cuba from North America. It

was last recorded in 1964.

SEMPER'S WARBLER ______ St. Lucia

(e)

Leucopeza semperi

Also:

Evidence suggests that there was formerly a "GIANT

BARN OWL" on

Hispaniola.

The Barn Owl (Tyto alba pratincola) and the closely-related

Ashy-faced Owl (Tyto

glaucops) continue on the island today.

Fossils in the Cayman Islands indicate that historically there were, on those

islands, some birds now extinct:

2 raptors (a large hawk and a caracara), and a second species of

bullfinch (an

endemic subspecies of the Cuban Bullfinch occurs there today).

EXTINCT BIRD SUBSPECIES IN THE WEST INDIES:

of the Uniform Crake: "JAMAICAN WOOD RAIL"

______ Jamaica (e)

Aramides c. concolor (last known

in 1881)

of the Hispaniolan Parakeet (or Conure): "PUERTO

RICAN CONURE" ______ Mona Island & mainland Puerto Rico

Aratinga chloroptera maugei (last

known in 1892)

of the Puerto Rican Amazon (or Parrot): "CULEBRA

ISLAND AMAZON" ______ Culebra Is. PR (e)

Amazona vittata gracileps

of the Burrowing Owl:

1) Speotyto cunicularia amaura ______ Antigua, Nevis, St. Kitts

(last known in 1900)

2) Speotyto cunicularia

guadeloupensis "GUADELOUPE

BURROWING OWL"______ Guadeloupe

(e) (last known in 1900)

of the Golden Swallow:

Tachycineta e. euchrysea ______

Jamaica (e) (last seen

in 1989, but maybe since)

of the House Wren:

Troglodytes aedon guadeloupensis ______

Guadeloupe (e)

Troglodytes aedon martinicensis ______

Martinique (e)

The subspecies of the

House Wren

on St. Lucia, the "ST. LUCIA WREN"

was, about 1970, thought to be extinct, but has subsequently been

rediscovered. It has been seen during FONT tours on that island.

of the Forest Thrush:

Cichlherminia lherminiieri sanctaeluciae ______ St. Lucia (e)

of the Puerto Rican Bullfinch

Loxigilla portoricensis grandis ______ St. Kitts (e)

(last known in 1900)

of the Jamaican Oriole

Icterus leucopteryx bardi ______ Cayman Islands (Grand Cayman) (e)

(last known in 1967)

References:

Threatened Birds of the World (a Birdlife International publication), Lynx Edicions, 2000, and later, updated information on the internet.